Iwas dubbed as having ‘hot foot’ for as long as I can remember (“Yuh cyah stay in one place fuh nutting!”). This ‘hot footed-ness’ had me travelling and living all over the world, and in so doing I would inevitably be asked the question, “But, where are you really from?”

Many of us who grew up in the diaspora know what is really meant by that when someone asks us, so we answer [insert ancestral country] instead of [insert city/country we actually live/grew up in]. But, there is something that feels amiss with this response. I know that I am more complex than that. Who am I really? What is my identity?

Today, our definition of “identity” derives itself mostly from Erik Erikson’s concept of an “identity crisis.” He defined “identity crisis” as “the condition of being uncertain of one’s feelings about oneself, especially with regard to character, goals, and origins…”

But then, what forms our character, goals and origins?

Over the course of our lives, we will internalize, both consciously and subconsciously, values or constructs simply because we are told to and because they seem natural. But if our identities are socially constructed, then they cannot be neutral. Indeed, society ultimately posits the superiority of one identity over another: men over women; whites over non-whites; straight over gay; wealthy over other classes; one religion over another… In fact all of these constructs – gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, etc. – determine, to a large extent, the roles that we ‘should’ be acting out, including whether we assume power within society or fall victim to systematic prejudices and unequal opportunities.

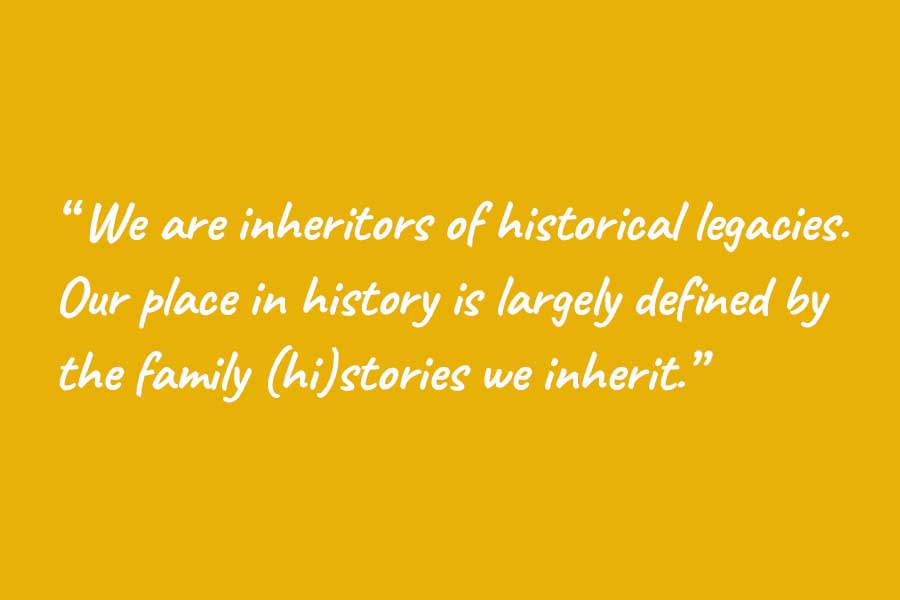

When I recorded my grandmother’s story (of escaping wars in China to marry my grandfather in an arranged marriage on the little island of Trinidad), I realized just how much her stories defined my own.

Understanding and studying our heritage — the good as well as the bad — is crucial to giving yourself a choice on how to interpret your own construct of self and your role in society.

Asking our loved ones, parents and grandparents to recount these stories can be difficult (“Dis big people business!”), especially considering the trials they might have lived through (Colonisation, Windrush, Barrel children, etc.).

But it is necessary to look back in order to chart a better future, especially for the generations to come. Exploring our past means we can gain a more grounded sense of identity. One that can be less swayed by the media or the populist politicians or the radical theologians. This means a less troubled mind, a less troubled world. A more empathetic world.

Every day we lose thousands of oral histories and records. Time is precious, and we, especially us from diverse parts of the world, cannot afford to wait until it’s too late. We all have a story to tell. Contact Plantain if you would like help.

*** Exclusive discount for RACA readers ***

Get a 5% discount on all Plantain services when you sign up for Plantain’s newsletter AND contact Plantain with the subject line RACA in the message.

Don’t delay. Start the journey to memorializing your family’s history today.